|

Durga Mata

One of the most impressive and formidable

goddesses of the Hindu pantheon-and one of the most popular-is the

goddess Durga. Her primary mythological function is to combat demons who

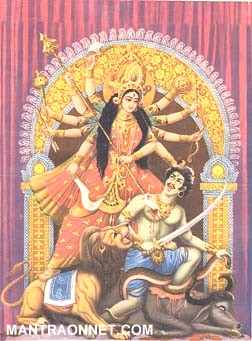

threaten the stability of the cosmos. In this role she is depicted as a

great battle queen with many arms, each of which wields a weapon. She

rides a fierce lion and is described as irresistible in battle. The

demon she is most famous for defeating is Mahisa, the buffalo demon. Her

most popular epithet is Mahisa-mardini, the slayer of Mahisa, and her

most common iconographic representation shows her defeating Mahisa.

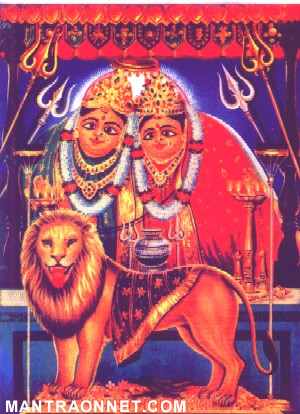

At a certain point in her history Durga becomes associated with the god Shiva as his wife. In this role Durga assumes domestic characteristics and is often identified with the goddess Parvati. She also takes on the role of mother in her later history. At her most important festival, Durga Pooja, she is shown flanked by four deities identified as her children: Karttikeya, Ganesh, Saraswati, and Lakshmi. It also seems clear that Durga has, or at least at some point in her,, history had, a close connection with the crops or with the fertility of vegetation. Her festival, which is held at harvest time, associates her with plants, and she also receives blood offerings, which may suggest the renourishment of her powers of fertility.

Durga s historical origin seems to be among the indigenous non-Aryan cultures of India. In addition to there beings no similar goddesses among the deities of the Vedic tradition, many early references to Durga associate her with peripheral areas such as the Vindhya Mountains, tribal peoples such as the Sabaras, and non-Aryan habits such as drinking liquor and blood and eating meat. Although Durga becomes an establishment goddess in medieval Hinduism, protecting the cosmos from the threat of demons and guarding dharma like a female version of Vishnu, her roots seem to be among the tribal and peasant cultures of India, which eventually leavened the male-dominated Vedic pantheon with several goddesses associated with power, blood, and battle.

The best-known account of Durga's origin, however, is told in connection with her defeat of the demon Mahisa After performing heroic austerities, Mahisa was granted the boon that he would be invincible to all opponents except a woman. He subsequently defeated the gods in battle and usurped their positions. The gods then assembled and, angry at the thought of Mahisa s triumph and their apparent inability to do anything about it, emitted their fiery energies. This great mass of light and strength congealed into the body of a beautiful woman, whose splendor spread through the universe. The parts of her body were formed from the male gods. Her face was formed from Shiva, her hair from Yama, her arms from Vishnu, and so on. Similarly, each of the male deities from whom she had been created gave her a weapon, Shiva gave her his trident, Vishnu gave her his cakra (a discus-like weapon), Vayu his bow and arrows, and so on. Equipped by the gods and supplied by the god Himalaya with a lion as her vehicle, Durga, the embodied strength of the gods, then roared mightily, causing the earth to shake.

The creation of the goddess Durga thus takes place in the context of a cosmic crisis precipitated by a demon whom the male gods are unable to subdue. She is created because the situation calls for a woman, a superior Warrior, a peculiar power possessed by the goddess with which the demon may be deluded, or a combination of all three. Invariably Durga defeats the demon handily, demonstrating both superior martial ability and superior power. On the battlefield she often creates female helpers from herself. The most famous of these are the goddess Kill and a group of ferocious deities known as the Matrkas (mothers), who usually number seven. These goddesses seem to embody Durga s fury and are wild, bloodthirsty, and particularly fierce. Durga does not create male helpers, and to my knowledge she does not fight with male allies Although she is created by the male gods and does their bidding and although she is observed and applauded by them, she (along with her female helpers and attendants) fights without direct male support against male demons-and she always wins. Durga's distinctive nature, and to a great extent probably her appeal, comes from the combination .of world-supportive qualities and liminal characteristics that associate her with the periphery of civilized order. In many respects Durga violates the model of the Hindu woman. She is not submissive, she is not subordinated to a male deity, she does not fulfill household duties, and she excels fit what is traditionally a male function, fighting in battle. As an independent warrior who can hold her own against any male on the battlefield" she reverses the normal role for females and therefore stands outside normal society. Unlike the normal female, Durga does not lend her power or Shakti to a male consort but rather takes power from the male gods in order to perform her own heroic exploits. They give up their inner strength, fire, and heat to create her and in so doing surrender their potency to her.

Because Durga is unprotected by a male deity, Mahisa assumes that she is helpless, which is the way that women are portrayed in the Dharma-sastras. There women are said to be incapable of handling their own affairs and to be socially inconsequential without relationships with men. They are significant primarily as sisters, daughters, and mothers of males and as wives. Nearly all forms of Durga s mythical exploits portray her as independent from male support and relationships yet irresistibly powerful. She is beautiful and seductive in appearance, but her beauty does not serve its normal function, which is to attract a husband. It serves to entice her victims into fatal battle. In short, this beautiful young woman who slays demons seeking to be her lovers and who exists independent from male protection or guidance represents a vision of the feminine that challenges the stereotyped view of women found in traditional Hindu law books. Such a characterization perhaps suggests the extraordinary power that is repressed in women who are forced into submissive and socially demeaning roles. In her role reversal Durga exists outside normal structures and provides a version of reality that potentially, at least, may be refreshing and socially invigorating. Durga s liminal nature is also evident in her favorite habitats and in some of her favorite habits. Nearly all of Durga s myths associate her with mountains, usually the Himalayas or the Vindhyas. One of her common epithets is Vindhyavasini, "she who dwells in the Vindhya Mountains." These mountainous regions are areas considered geographically peripheral civilized society and inaccessible except through heroic efforts. The Vindhyas, in particular, are also regarded as dangerous because of- the violent and hostile tribal peoples who dwell there. Indeed, Durga is said to be worshiped by tribal groups such as the Sabaras. In this worship, furthermore, she is said to receive (and to enjoy) meat and blood, both of which are regarded by civilized Aryan society as highly polluting. In the Devi-mahatmya Durga is also described as quaffing wine during battle in her fight with Mahisa and as laughing and glaring with reddened eyes under its influence. In the concluding scene of the Devi-mahatmya her devotees are instructed to propitiate her with offering of their own flesh and blood. Durga s preference for inaccessible dwelling places, her worship by tribal peoples, her taste for intoxicating it ink, meat, and blood, her ferocious behavior on the battlefield, and her preference for the flesh and blood of her devotees convey a portrait of a goddess who stands outside the city issued order of dharnia; her presence is to be found only after stepping out of the orderly world into the liminal space of the mountainous region where she dwells. Reinforcing Durga s tendencies to the antistructural or liminal are certain associations with negative, or at least inauspicious, qualities or powers such as sleep, hunger, and may a (in the sense of delusion). In the Mahisa episode of the Devi-mahatmya she is called she whose form is sleep, she whose form is hunger, she whose form is shadow, and she whose form is thirst. These associations are particularly emphasized in versions of the myth that tell of Durga s aid to Brahma and Vishnu against the demons Madhu and Kaitabha. In this myth as told in the Devi-Shatmya Madhu and Kaitabha are born from Vishnu s ear wax. They threaten to kill the god Brahma, who in turn has been born from a lotus sprung from Vishnu s navel. Brahma appeals to the goddess in the form of sleep to come forth from Vishnu so that he will awaken and slay the demons. Throughout the episode the goddess is called Mahamaya, the power that throws people into the bondage of delusion and attachment. Indeed, Vishnu is successful in slaying Madhu and Kaitabha only because the goddess deludes them into offering Vishnu a boon; he accepts and asks that they permit him to slay them. She is also called great delusion (Mahamoha); the great demoness (Mahasuri); the black night, the great night, the night of delusion; darkness (Tamas); the force at seizes those of knowledge and leads them to delusion; and the cause of bondage in the world. The entire Madhu-Kaitabha episode as told in the Devi-mahatmya hinges on Vishnu s helplessness as long as he is pervaded by the goddess, whose primary effect on him is to keep him unconscious. In this episode, then, the goddess has numbing, deluding, dark qualities, even though she is called by many positive terms. Again, Durga s role vis-a-vis Vishnu seems exactly the opposite of the normal role of a goddess as a male deity s Shakti, the power that enables the god to act in the world, in this myth Vishnu is only enabled to act when the goddess leaves him. She does not empower, enliven, or strengthen Vishnu; she puts him to sleep, reducing him to powerlessness.

Counterbalancing Durga s liminal, peripheral nature, which at times seems to threaten dharmic stability and to inhibit the spiritual quest for moksha, is her role as protector of the cosmos. Dominating her mythology is her role as the destroyer of demons who have usurped the position of the gods. As a great warrior she is created by the gods and acts on their behalf. While she is often said to transcend the male gods who create her and to excel them on the battlefield, she acts for their welfare. In doing this he acts to maintain or restore cosmic harmony and balance. The theology underlying Durga s appearances and exploits is clear in the Devi-mahatmya, the most famous text extolling her deeds. Durga is said to underlie or pervade the cosmos; to create, maintain and periodically destroy it according to the rhythmic sequences of Hindu cosmology; and to assume different forms from time to time when cosmic balance is threatened by enemies of the lesser gods. The Devi-mahatmya puts the matter succinctly: Though she is eternal, the goddess becomes manifest over and over again to protect the world. The Devi-mahatmya itself relates three of Durga s cosmic interventions on behalf of the gods: the battle with Madhu and Kaitabha; the battle with Mahisa and his army; and the battle with Sumbha and Niibumbha and their generals, Canda, Munda and Raktabija. The text also refers specifically to five other appearances of the goddess and implies that she is incarnate in many more forms. The myths that are told in detail in the Devi-mahatmya conform to a structure that underlines Durga's role as the-upholder and protector of the dharmic order. Because the myths are cast in traditional structure, they also make the point that Durga transcends the great male gods of the Hindu pantheon, who in other texts usually have the central role in these myths. . The structure to which the demon-slaying myths of Durga conform is found throughout Hindu mythological texts and is consistent despite the specific deity who is featured in the myth. In basic outline the structure is as follows:

In the Madhu and Kaitabha myth and the myth of Sumbha and Nisumbha, Durga is petitioned to help the gods, whereas in the Mahisa myth she is specially created by the gods. In the Mahisa and Sumbha and Nisumbha myths the goddess acts a direct, active part in the battle itself, demonstrating her superior martial skills against her opponents, in the Sumbha and Nisumbha myth she also creates helpers in the form of ferocious goddesses. In all three episodes the gods collectively praise Dui~ during the battle or after she has defeated the demons.

The theology underlying Durga's cosmic interventions and the structure of the demon-slaying myths thus conform to the well known Hindu ideas and forms. The idea of a deity s descending to the world from time to time in various forms to maintain the balance of cosmic order is a central Vaisnavite idea. Ever- since the time of the Bhagavad-gita the idea of Vishnu's descending to the world in different forms in order to combat disorder has been well known in the Hindu tradition. Durga, in the Devi-mahatmya, is heir to this avatara theology. Infact, in many ways Durga's is a female version of Vishnu. She, like him, creates, maintains, and destroys the world; intervenes on a cosmic scale whenever disorder threatens to disrupt the world in the form of certain demons; and is approached by the other gods in distress. This conformity to a well known type of theology does not detract from Durga's appeal, power, or prestige: Oh the contrary, fey creating her in this familiar role and by telling her myths according to a familiar structure, the author of the Devi-mahatmya underlines Durga s supremacy and might. Durga's role as cosmic queen is complemented by her role as a personal comforter who intervenes on behalf of her devotees. Near the end of the Devi-mahatmya, after the world has been restored to order, Durga herself says that she is quick to hearken to the pleas of her devotees and that she may be petitioned in times of distress to help those who worship her. She mentions specifically forest fires, wild animals, robbers, imprisonment, execution, and battle as some threats from which she will save her devotees. At the end of the Devt-mahatmya, after being petitioned by two of her devotees (part of whose petition has included offering their own blood to the goddess) she appears before them and grants their desires. To one she returns his wealth and kingdom and to the other she grants ultimate liberation. Durga, then, is not just a powerful, transcendent force whose sole concern is maintaining the cosmic rhythms, who is moved to action only when the world itself is threatened. She is attentive to the needs of her devotees and intervenes on their behalf if asked to do so. She is a personal savior as well as a great battle queen who fights to defeat the enemies of the gods. When Durga is called Maya, or equated or associated with it, both connotations--delusion and creation-are suggested. Like Vishnu, Durga creates the world through her extraordinary power, but then she be-witches the creatures she has created. Underlying this apparently incomprehensible "game" is the idea of divine lila (sport, play, or dalliance), according to which the gods never act out of necessity but only out of a sense of play. Unlike mere mortals, the gods (in this case Durga) act not from pragmatic motives but only to amuse themselves or to display themselves. The way in which Durga s defeat of Mahisa is often depicted in Indian art suggests this theme. Typically she is shown bringing a blizzard of weapons to bear on the hapless demon, who is half-emerging in his human form from the carcass of his former buffalo form. Durga's many arms are all in motion, and she is a perfect vision of power in action. Her face, however, is calm and shows no sign of strain. For her this is mere sport and requires no undue exertion. It is a game for her, it is Irla. She enters into the cosmic struggle between the lesser gods and the demons because it pleases her, not out of any sense of compulsion. Durga's identification with prakrti and with the earth itself makes another theological point. Prakrti is the physical world as well as the inherent rhythms within this world that impel nature to gratify and produce itself in its manifold species. Prakrti is both the primordial matter from which all material things come and the living instincts and patterns that imbue the material world with its proclivities to sustain and recreate itself in individual beings. As prakrti, then, Durga is inextricably associated with the physical world, the world she creates, sustains, and protects in her various forms. Durga s identification with the world is unambiguous. The Devi-mahatmya makes a point at several places to say that she is the world, she is all this. As the earth itself she conveys cosmic stability. She is the foundation of all creatures and that which nourishes all creatures. As the embodiment of f the earth she supports, protects, and mothers all beings. As Sakambhan she provides the world with food from her own body. In her role as cosmic queen, warrior goddess, and demon slayer, Durga in effect protects herself in her aspect as the-earth itself. As immanent in the world Durga is equated with the earth. As transcendent, she is the heavenly queen who descends from time to time to maintain harmony on earth. Durga's association or identification with sakti, maya, and prakrti lends to the great demon-slaying goddess an immediate, tangible dimension. As an expression of these ideas she is identified with the creation itself. Her presence is affirmed to pervade and underlie the actual world in which people live, and her power and strength are affirmed to imbue all creatures with the will to prosper and multiply. The Worship Of Durga One of the most important festivals in North India is Durga Pooja, which is celebrated in the autumn during the month of Asvin. The festival takes place over a period of nine days and is often called the Navaratra festival. The central image of the festival shows Durga slaying Mahisa The iconographical details of the images are usually faithful to the scene, as described in the Devi-mahatmya and other scriptures. Durga has many arms, each of which bears a weapon; she stands on her lion vehicle; and she is thrusting her trident into the chest of Mahisa who is in human form, half-emerged from the carcass of a slain buffalo. During the festival it is customary to recite the Devi-mahatmya in its entirety several times. The Durga Pooja festival clearly asserts Durga s central role as a battle queen and the regulator of the cosmos. In part, at least, the festivities celebrate Durga s defeat of Mahisa and the restoration of cosmic order. This festival, in which Durga is worshiped in the form of a mighty warrior goddess, seems to be, or to have been until recently, part of a pattern of worship undertaken by rulers for success in battle. The festival of Dassera, which falls on the tenth tithi (lunar day) of the bright half of Asvin and thus immediately follows Durga Pooja (which occupies the first through ninth tithis of the bright half of Asvin), was in many parts of India primarily an occasion in which to celebrate military might and royal power and to petition for military success in the coming year. Worship of weapons was also a part of the festival in many cases.

"The Dassera is likewise the soldier's feast. Princes and soldiers offer the most solemn sacrifices to the arms which are made use of in battle. Collecting all their weapons together, they call a Brahmin purohita, who sprinkles them with tirtham (holy water) and converts them into so many divinities by virtue of his mantrams. He then makes Pooja to them and retires. Thereupon, amidst the beat of drums, the blare of trumpets and other instruments, a ram is brought in with much pomp and sacrificed in honour of the various weapons of destruction. This ceremony is observed with the greatest solemnity throughout the whole Peninsula. . . . It is known by the special name of ayuda-Pooja (sacrifice to arms), and is entirely military." Alexander Forbes, who wrote in the second half of the nineteenth century, described Dassera among the Rajputs: "The Rajpoot chiefs, on the evening of Dussera, worship also the Fort-Protectress, the goddess Gudeychee. On their return from the Shumee worship into the city, they join together in bands, brandishing their spears, galloping their horses, and enacting in other ways the part of an army taking the field."" Although the worship of a goddess is not always part of Dassera celebrations, there are many indications in ritual and mythological texts that the annual (usually autumnal) worship of a warrior goddess, often specified to be Durga, was part of festivals associated with military success. Mantras to be uttered by kings on the occasion of Dassera, for example, sometimes invoke a goddess. In the Dharmasindhu the king is to speak this prayer: "May Aparajita [the unconquerable one] wearing a striking necklace and resplendent golden girdle and fond of doing good bestow victory on "24 In the Nirnayasindha this prayer is to be said at the time of blessing weapons: "0 goddess, ruling over gods! may my army divided into four sections (elephants, chariots, horsemen, and foot-soldiers) attain to the position of having no enemy left in this world and may victory come to me everywhere through your favour." An eleventh- or twelfth-century Jain text, the Yasatilaka of Somadeva, mentions the worship of Aparajita, who is also called Ambika. She is said to give victory in war and to be present in the king s weapons." The text also says that she is worshiped on Mahanavami, which is the last day of Durga Pooja. Some Puranas, furthermore, say that mrajana, the worship of weapons, is held on Mahanavamr. In the Prakrit drama Gaudavaho, King Yasovarman undertakes a military campaign in the autumn. Shortly after beginning his march he reaches the Vindhya Mountains and there undertakes the worship of the goddess Vindhyavasini (she who dwells in the Vindhyas), an epithet of Durga in some texts".

The worship of Durga also came to be associated with the military success of both the Pandava brothers in the Mahabharata and Rama in the Ramayana. Although her worship by the heroes was not part of either epic tradition initially (the incidents are not found in the critical editions of either epic), a tradition has developed that insists that the worship of Durga was necessary to the success of the heroes in both epics. Durga is worshiped twice in the Mahabharata: in Virata-parva by Yudhishthira and in Bhisma-parva by Arjuna. In the latter case the occasion of Durga s praise is clear. The setting is just before the great battle that is the highpoint of the entire epic. Krishna instructs Arjuna as follows: "0 one having great arms, standing in the face of battle, say a hymn to Durga for the purpose of defeating your enemies". The hymn that Arjuna then offers is full of references to Durga s military might and prowess. The goddess appears to Arjuna and promises him victory, after which the text says that anyone who hears or recites the hymn will be victorious in battle. The placement of the second hymn to Durga in Virata-parva is more difficult to understand. The Pandava brothers have just emerged from twelve years of exile in the forest and are about to begin a year of life in the world during which they must remain in disguise lest their enemies discover them. Before entering the city of Virata and taking up their disguises they hid their weapons in a sami tree near a cremation ground. Yudhishthira asks Durga for protection from being discovered during the coming year and for later success against their enemies. She appears at the end of the hymn and grants his wishes. It seems that the hymn was placed at this point in the text because worship of a sami tree on the outskirts of a town is often a part of Dassera festivals. The author or editor of the hymn probably thought this an appropriate place to insert a hymn to Durga for military success.

|